In 2014, Joe Duggan started reaching out to climate scientists to ask them a question: how did climate change make them feel?

“I was just blown away when I started getting the letters back,” he says.

Duggan, a science communicator at Australian National University, set up a website and starting publishing the mostly handwritten responses.

“[Professor] Katrin Meissner was one of the first, and her letter really hit me. It was so … unscience-y. Almost poetic.”

“It makes me feel sad. And it scares me,” Meissner wrote.

“It scares me more than anything else. I see a group of people sitting in a boat, happily waving, taking pictures on the way, not knowing that this boat is floating right into a powerful and deadly waterfall.”

In the end, more than 40 scientists responded – many leaders in their field. Some wrote neatly on lined notepaper, others scrawled on the back of student papers they were marking.

“It became a big part of my life,” Duggan says. “I felt a little bit out of my depth. It took its toll on me and in the end I felt I had to step away. I went into my shell and pretty much turned off my phone for three years.

“But I’ve got some emotional resilience back now. My partner and I found out we’re pregnant – due in August. I don’t want that kid to grow up asking why we didn’t actually do anything.”

So Duggan has returned to his “passion project” – Is This How You Feel – by asking the scientists to write again. Have their feelings changed in the intervening years?

The first 10 return letters are emotional outpourings of despair, hope, fear and determination in the age of the climate crisis, from the people helping the world understand its impacts while also being mums, dads and grandparents.

Since the first letters were written, two Australian correspondents Tony McMichael and Michael Raupach have died. But Duggan is trying to reach their family members to see if they can keep the legacy moving.

Meissner, now director of the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of New South Wales, didn’t hesitate to respond partly because “it was the right thing to do”.

“But also because we have not been very good at communicating climate science to the public and I believe that it is my duty as a citizen to alert people to the urgency of the situation.”

But does Meissner think there’s a risk in scientists lifting their veil of cool objectivity to show their personal feelings? Could it cause some to question their objectivity?

“I actually think that the opposite is the case,” she says. “When I saw the whole collection of letters a few years ago, I was surprised by the number of colleagues who had participated.

“We are talking here about world-leading scientists, people who built their career on facts and data, who are spending their lives questioning every result they find, over and over again. People who are continuously challenging the status quo. People who are trained to be objective.

“When these people start to speak up about their feelings, about being frustrated, desperate, worried, angry or scared, then we really should listen very carefully.”

Duggan wants anyone who has read the letters to write their own, and share them. Here are some excerpts from the latest scientist letters from Duggan’s project.

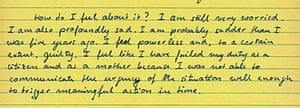

Prof Katrin Meissner

How do I feel about it? I am still very worried. I am also profoundly sad. I am probably sadder than I was five years ago.

I feel powerless and, to a certain extent, guilty. I feel like I have failed my duty as a citizen and as a mother because I was not able to communicate the urgency of the situation well enough to trigger meaningful action in time.

What we are doing right now is an uncontrolled, risky experiment with the planet we live on.

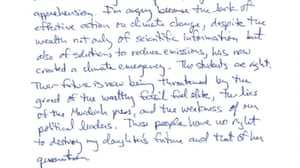

Prof Will Steffen, Australian National University

I’m angry because the lack of effective action on climate change, despite the wealth not only of scientific information but also of solutions to reduce emissions, has now created a climate emergency.

The students are right. Their future is now being threatening by the greed of the wealthy fossil fuel elite, the lies of the Murdoch press, and the weakness of our political leaders. These people have no right to destroy my daughter’s future and that of her generation.

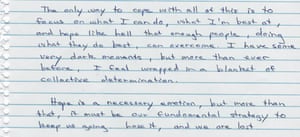

Prof Lesley Hughes, pro vice-chancellor, Macquarie University

My emotions haven’t really changed since I last wrote one of these letters, but things around me have. The beacon of light that is Greta Thunberg, speaking truth to power. Our own wonderful, passionate school kids taking to the streets, making me cry with pride.

The only way to cope with all of this is to focus on what I can do, what I’m best at, and hope like hell that enough people, doing what they do best, can overcome.I have some very dark moments, but more than ever before, I feel wrapped in a blanket of collective determination. Hope is a necessary emotion, but more than that, it must be our fundamental strategy to keep us going. Lose it, and we are lost.

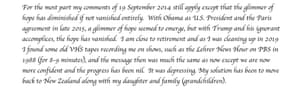

Dr Kevin Trenberth, National Centre for Atmospheric Research (US)

For the most part my comments of 19 September 2014 still apply except that the glimmer of hope has diminished if not vanished entirely. With Obama as US president and the Paris agreement in late 2015, a glimmer of hope seemed to emerge, but with Trump and his ignorant accomplices, the hope has vanished.

I am close to retirement and as I was cleaning up in 2019 I found some old VHS tapes recording me on shows, such as the Lehrer News Hour on PBS in 1988, and the message then was much the same as now except we are now more confident and the progress has been nil. It was depressing. My solution has been to move back to New Zealand along with my daughter and family (grandchildren).

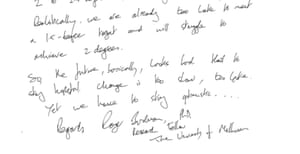

Dr Roger Bodman, University of Melbourne

Realistically, we are already too late to meet a 1.5 degree target and will struggle to achieve 2 degrees.

So, the future, basically, looks bad. Hard to stay hopeful. Change is too slow, too late.

Yet we have to stay optimistic.

Dr Jennie Mallela, Australian National University

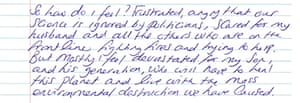

Dear Joe,

Climate Change feels very real and I think this summer we reached a tipping point in Australia. As I write this my husband, a bushfire fighter, is battling a fire in Canberra and I’m working from home as a freak hailstorm destroyed my car three days ago. In four days, we’ve been smashed by our climate: hail, extreme winds, toxic smoke and fire.

…. So how do I feel? Frustrated, angry that our science is ignored by politicians, scared for my husband and all the others who are on the frontline fighting these fires and trying to help.

But mostly I feel devastated for my son, and his generation, who will have to heal this planet and live with the mass environmental destruction we have caused.

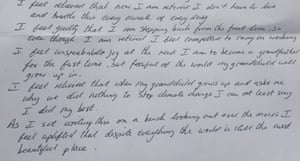

Prof Dave Griggs, Monash Sustainable Development Institute

I feel scared for the future when faced with simple downright ignorance from some political leaders.

I feel tired, tired that in spite of bushfires, floods etc I still seem to be banging my head against a brick wall to convince people that the threat of climate change is severe.

I feel relieved that now I am retired I don’t have to live and breathe this every minute of every day.

I feel guilty that I am stepping back from the frontline, so even though I am retired I feel compelled to carry on working.

I feel unspeakable joy at the news that I am to become a grandfather for the first time, but fearful of the world my grandchild will grow up in.

I feel relieved that when my grandchild grows up and asks me why we did nothing to stop climate change I can at least say that I did my best.

As I sit writing this on a bench looking out over the moors I feel uplifted that despite everything the world is still the most beautiful place.

The full collection of letters is available at Is This How You Feel.